In questo articolo il tema è il Mercato. Si sondano le radici etimologiche del termine, nonché il concetto che del Mercato si aveva nel Medioevo e nell’età moderna. Oggi le cose sono molto cambiate, ed il Mercato va ad interferire con l’interesse degli Stati. Le fonti citate sono di tutto rispetto, e vanno da Sant’Antonino, a Galbraith, da Polany a Stiglitz.

According to Benveniste’s etymological studies, Negotium is the Latin translation of the Greek word askholìa. This important Greek word means both having no time, and to be busy. The adjective áskholos (derived from askholìa) means one who has no time, one who is busy. He who has no time in Latin was called negotiosus, an adjective corresponding to Greek áskholos. The Greek language also coined skholé, the opposite of askholìa, which means time available. The Greek word askholìa meant so “activity”, but did not indicate specifically commercial affairs. In fact, negotium, negotiosus and negotiositas have their root in the Greek term pragma (thing). The Latin verb negotiari translated the Greek verb prasso or praxo, which had the meaning of business deal.

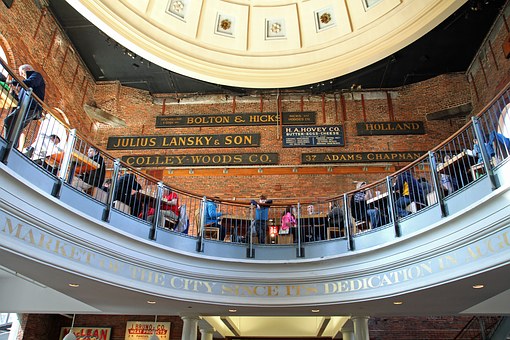

Galbraith stated that the market was the place where buyers and sellers meet physically to exchange food, clothing, livestock and manufactured goods of all kinds. Today the market can be described in terms of an abstract concept in which the purchase or sale of specific goods or services is implemented, but with no reference to a geographical location. The market today is therefore an abstraction. Galbraith also stressed that several American captains of industry talk earnestly about their complex financial transactions in the financial markets, which however are places where they have never set foot.

The marketing process was called commercium (business, trading) in the mercantile market economy of the classical and modern world. Commercium derives from the Latin word merx (goods, wares), from which is derived mercator (trader, dealer, merchant). Merx means exactly trafficked thing, or goods offered for sale at a specific price ( Latin pretium). The etymology of price (pretium) seems to be from the Latin word inter-pret (Benveniste, p. 91), which means bargaining or price based upon mutual agreement of the parties.

But there is one very important difference between the ancient and contemporary market to consider. While today world economy is based on a free market, in medieval and modern times things were very different. As M. Bloch stressed, traders obtained their means of subsistence from the difference between the selling price and the purchase price (the trading margin) or offering personal loans at a very high interest rates. In medieval and modern times the interest rate was considered as usurious, and all Roman Catholic theologians also interpreted it as immoral behavior.

San Antonino’s works (1389-1455) like De Statu mercatorum ( On Market Status), De Turpi Lucro (On Shameful Profit) and De Usura in emptione et venditione (Treaty of Bargain and Sale), stand out in this regard,

“Although not a very original thinker, San Antonino wrote with case and was versed in the extant canonistic and theological literature. His works contain an excellent summary of the controversy, then raging, about the lawfulness of interest-bearing shares in the public debt. With regard to value and price, he takes over the theory of San Bernardino without modification; yet he has often received underserved credit as the first to mention utility.” (R. De Roover).

However, things changed slightly over time, in the sense that several theologians thought that who had risked his own capital should be repaid, because of money “ habet quondam seminalem rationem, quam communiter capitale vocamus” [ money has its original cause of profit, which we commonly call capital ] (San Bernardino). Precisely because both trade and earning interest in loans were deemed immoral, the market system was tightly controlled at the birth of the modern nation-state.

For example, the precise place where economic transactions took place and the regulation of marketing hours of opening and closing had been established very accurately, because the market was considered to be a separate place with its own separate laws and moral principles, dominated by private interests. The separation between market and state was because state apparatus served public needs not private interests, and they should not interfere with national interests.

The distinction makes it clear that the Ancients realized the huge difference that existed between private interest and national interests, not admitting of an easy extension of Market boundaries. But today, the exact opposite happens, allowing the Market to interfere with national interests, disrupting governments and social institutions. This means that, as Polany said, “Instead of the historically normal pattern of subordinating the economy to society, their system of self-regulating markets required subordinating society to the logic of the market […] It means no less than the running of society as an adjunct to the market. Instead of economy being embedded in social relations, social relations are embedded in the economic system.”

This, of course, constitutes an aberration of actual globalization.

“Is market society the Fin of history?”

“ The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands, ” Fukuyama said. And Stiglitz added: “I am sure Polanyi would suggest that the challenge facing the global community today is whether it can redress these imbalances—before it is too late.” (Stiglitz, p. XVII).

I’d like to add something to what has been said so far, that is such an aberration would require a strong finish. The state apparatus is distinct from the market, and it should thus defend its prerogatives.

Sources:

E. Benveniste, Vocabulario de las instituciones indoeuropeas, Taurus, 1983, p. 93.

O. Pianigiani, Vocabolario etimologico della lingua italiana, Società editrice Dante Alighieri, 1907, M-Z. Vol. 2, p. 1051. Prammatica. Latin Pragmatica, Greek Pragmatiké.

John Kenneth Galbraith, Almost Everyone’s Guide to Economics. London, Penguin Books, 1981.

On Commercium and merx, Pietro Cerami, Diritto commerciale romano: profilo storico. Giappichelli, 2004, pp. 15-17.

M. Bloch, La società feudale, Einaudi, Torino 1971 (Fist Edition, 1949).

R. De Roover, “Scholastic Economics: survival and lasting influence from the sixteenth century to Adam Smith.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, LXIX, 1955, p. 16.

R. Gagnier, “Is Market Society the Fin of History?” The Insatiability of Human Wants: Economics and Aesthetics in Market Society, Chicago & London, The University of Chicago Press, 2000, p. 61.

K. Polanyi, The Great transformation, Edited by J. E. Stiglitz & F. Block, Beacon Press, 2001, p. XXIV.

On San Antonino and San Bernardino, see A. Spicciani, “Note su Sant’ Antonino economista.” Economia e Storia, aprile-giugno 1975, 2, pp. 171-192, p. 175, 186.